The truth of the matter is that people want convenience. We have always strived towards convenience and ease. Instant gratification being the aim, it is clearly demonstrated in the developing technology of today. Smartphones, touchscreens, wireless, digital files, etc. All this derives from the aforementioned motive. If this is so then why is there a counter-culture that keeps alive relics now seemingly defunct?

In fact, this underground movement is not limited to an unknown minority. There are millions of people completely dedicated to hobbies involving analogue devices. Take the example of music: Despite there being immense possibilities for listening to your favourite songs with ease, many insist on returning to something we are supposedly trying to abandon. Countless vinyl are sold on a daily basis – I became aware of this more so at university, where the enthusiasts in these small shops were mainly my age. This is something to mention. Another baffling aspect of this counter-culture is that it is almost exclusively comprised of young people. Anyone aged twenty to thirty now would have never used a record player in the days of yore. If this is so, why then are so many youths entranced with this era of technology? Perhaps that’s the key word: Entranced.

I will admit that I have not interviewed any specific person about this topic, nor have I conducted a large sample-based study that would confirm to me that my hunches are true. Furthermore, it is logical that a lot of people older than thirty are seriously involved in these communities, in addition to the younger group. The point here is that the older population has more reason to exist within this counter-culture, as goes the saying: old dogs, new tricks and so forth. It is the youth that confounds it all. This can be explored with the word stated just in the last paragraph. Entrancement by definition is to fill someone with wonder or delight, holding their entire attention. By all means, those who are already familiar with record players would definitely feel joy or delight but not wonder – that signifies an essence of mysticism experienced by the inexperienced, aka the young. Consider this; imagine you are walking down the street and you need to know the time. You ask someone walking by and they kindly raise their hand and peer at, not a watch but a wrist sundial. We know these things never existed as far as I’m concerned, but wouldn’t it leave you flat on your back! Straight off the bat you would be asking the man how it worked or where he got it from. The same (well not exactly the same) is felt by a college kid who sees someone adjusting the needle on top of this huge disc, only for sound to soon follow the action.

Returning to the conversation about convenience, part of the question can be explained through this idea. Yet surely, that cannot be the only reason for a person, who has the ultimate form of technology at their fingertips, to resort to using theoretically antiquated equipment – the novelty would soon wear off. Then what else? Something can be said about the difference in result. When you compare the sound of a vinyl to a streamed song, the stark disparity is immediately apparent. It doesn’t mean that the vinyl is necessarily better than the latter, only that it offers a uniquely valuable experience, one that is lost with constant innovation. Heck I’ll go even further, compare the CD to the streamed song and you will find the former is superior (wav formats continue to beat compressed streaming files in terms of fidelity). Therefore, one can comprehend the practical use of the CD. However, the vinyl is definitely grainier and has the tendency to jump. Again, it is this rudimentary yet pioneering effort to pack a song into a black disc that has been romanticised over time. Nostalgia keeps those with memories attached and wonder attracts those who have heard legends of these devices.

Something must be said about the true quality of analogue media. This is what these communities highly value. When you snap a picture with an £800 camera now, supposing you know how to use it, you will get a substantially high definition picture of your subject matter. There will be some hiccups you will probably need to readjust for but that can mostly be attended to in post-production. Rewind the reel, if you will, forty years ago and you get a camera with many more dials and whistles. Granted, not so user-friendly, but infinitely more tactile and fun. Added on to that is the element of film and the texture it gives to your photographs. Nonetheless, although digital files will always be more practical, film is sought out by photographers today. Many directors are rife purists and insist on only shooting with film, while others are more lenient in the cause.

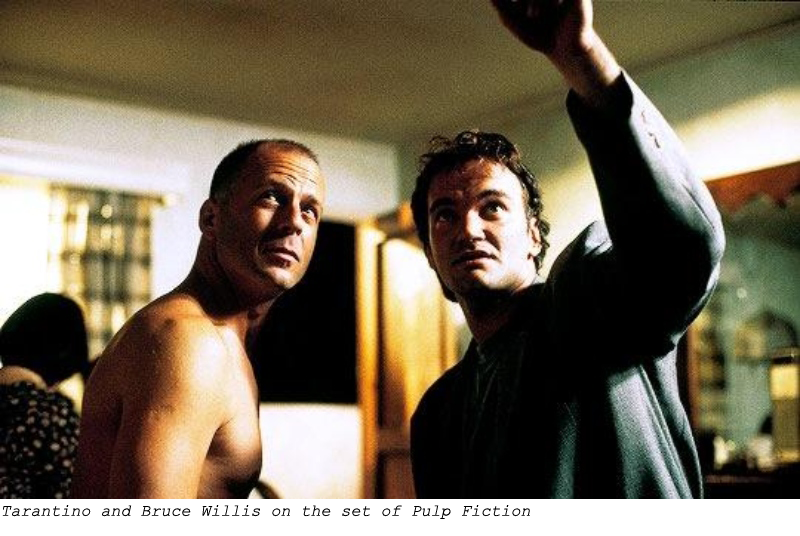

Quentin Tarantino shoots with film (The Hateful Eight was shot on Panavision’s 70mm, the same type used on Ben-Hur) and is known for recapturing classic cinema of the sixties and seventies, all while representing it in his own style and thereby giving it new life. He was quoted saying: ‘As far as I’m concerned, digital production…is the death of cinema as I know it.’ Obviously, this may seem extremist, and it may be. The cinematographer Roger Deakins, who is older than Tarantino, shoots digital in his later career. He has said ‘It’s not because I can do it digitally…not because it’s easier, because it gives me more options.’ Tarantino has stated that the illusion of film is the key to its allure, saying ‘I’ve always believed in the magic of movies…there is no movement in movies at all, they are still pictures, but when shown at twenty-four frames per second, through a lightbulb, it creates the illusion of movement…to me, that illusion is connected to the magic of movies.’

It seems that there is novelty still to be found in these traditional methods. Possibly that feeling of tradition is amplified by the film vs digital debate. Tim Roth, an actor frequently in Tarantino films, while interviewed for the film The Hateful Eight, said ‘We’re not in a hard drive, we’re in a movie.’ This element of ‘doing things the right way’ can account for the wider population of the counter-culture. Analogue media resembles the struggles and successes of those who came before and thus have paved the path we tread. There is a certain sentimentality intertwined with the process. But also tradition has its meaning other than protocol. Tradition often involves a procedure, a ritual which is performed during the activity. One would describe this ritual as bulk, excess, or redundant when compared to the bang and you’re off technology we have today.

Nevertheless, we must not so easily dismiss these practices. Some would argue that this is precisely what is fun about the activity itself. A thought experiment (last one, promise): You have an old fashioned automobile, one that should have been made into an ashtray before Nixon’s resignation. After a few minutes of reading, you try and start it up. You spin the little crank on the grill (I have no idea what I’m talking about) and pull the choke, eventually hearing a chuckling gurgle from the exhaust. Pulling the handbrake, you ride off at 30 km/h. Now you own a fully automated Tesla and it starts before you’re even in the garage. It drives you to work and wishes you a nice day. Sure, a talking car would be pretty amazing but there’s a soullessness about it all. Yes, the Tesla would blaze circuits around the old town car but there’s joy in the endeavour.

Funnily enough, Fujifilm is one company that has recognised this rise in affinity for the analogue. If you happen to hop on their website, you will immediately see that most of their range consists of cameras with the very dials and whistles mentioned earlier. It seems that they understand what their customers want, and that is to use a Fujifilm! Surely, when you finally save up to go to a Wagner opera, you aren’t met with a dubstep rendition of the play. That would be a rip-off. People want consistency, consistency in the legacy of the brands they have known their whole lives. Some have grown up with it and others have inherited this loyalty through family generations. These cameras aren’t exactly the same ones you would buy fifty years ago, they are better. Fujifilm has smartly kept what makes their cameras unique, aka the appearance and handling, but has brought the efficiency all the way up. These cameras are now digital and mirrorless, this means near-to-zero mechanical lag or malfunctions. Pictures are clearer and you can snap countless more without ever changing a reel. However (and this is a big however) when you pick one up, you are still holding a Fujifilm. The ergonomics are also improved, meaning lighter weight and slimmer design. Yet, you still get the same experience. Lastly, and probably most fascinating, Fujifilm have implemented colour profiles that resemble the very same film reels they offered back in the day. Called film simulation, settings such as Classic Chrome can really make your pictures look like film, even to the point of adding grain.

Why would people do this? Well, the last paragraph could probably be summarised with this one sentence from Fujifilm ‘Great images need great colour and Fujifilm’s outstanding legacy in colour science, perfected by combining more than 85 years of expertise and knowledge, delivers on every image that is created.’ It is clear how they emphasise their legacy here. Or how about ‘Film simulation options deliver warm skin tones, crisp blue hues of the sky and vivid green of lush greenery exactly as your mind remembers in your memory.’ That last part really hits it home, I think. All this being said, it is important to realise the very ease of digital mediums. Tarantino, depicted as a sheer loather of the digital, has also said ‘The good side of digital is the fact that…a young filmmaker…can actually now just buy a cell phone, and if they have the tenacity to actually…come up with an interesting story…they can actually make a movie…Back in my day you at least needed 16mm to do something like that, which was a Mount Everest most of us couldn’t climb.’ There you go. Although he does end it by retorting to himself ‘Now, why an established filmmaker would shoot on digital, I have no f**king idea.’ – smooth.

Speaking for myself, the concept for this article came out of frustration. Not with the way technology is today – although I do have my qualms – but with myself. I felt a lack of something in my life, as if it was all too easy. What’s the capital of… Google: ‘did you mean Uruguay? Montevideo.’ Strangely I wasn’t even on Google. Hearing old stories about how my dad had to call overseas to the UK, who then contacted their branch in the US, just to get a book he couldn’t buy locally.

The copy was shipped over and when my dad got it you can bet, he was pleased. There’s tradition and then there’s endeavour, perseverance. Nowadays, what? I’ll just buy it from kindle or download it illegally from pirate bay. Don’t get me wrong, pirating is adventurous, but I’d rather do the plank walking kind with the sea breeze blowing on my eyepatch.

My aunt was once so satisfied with a chocolate she had eaten (talk about simple times) that she wrote a letter to Cadburys thanking them. They wrote back! Sent her a bar as a complement. That’s some Willy Wonka story. Today, what? Cadbury’s would probably retweet your message and give you a complementary like. It’s free publicity for them anyway. Besides, you wouldn’t probably even take the time to tweet it, let alone find a pen and an A7 size envelope. If you’ve ever seen Miracle on 34th Street, you remember the scene when nobody could believe that anyone would do a gesture of good will, no strings attached. Eventually they all got into the spirit of Christmas, but that’s what Cadbury’s did for my aunt, a gesture of good will. She would spread the word of course and they would receive a few more customers, but that act meant more to her than what it could ever do for them.

Old man rant over. Yikes! I’m only twenty-eight. What I suppose I’m saying is that maybe all this effort to get back to a time and place when things were slower means something. Perhaps today’s youth feels we have gone too far. I know I’ve felt that. Moreover, I remember when I became an adult, thinking how, while a child, I expected life to be different. Like many of my peers, I felt I’d been robbed of an experience. A life that was simpler and more meaningful. I know that cannot be found in these superfluous objects, but there is something that they give us. We seek this meaning and attempt to slow time by adding obstacles. Through these small victories we find true fulfilment.

References

'The Hateful Eight:' Shooting on Film in the Digital Age. (2015). [Video]. Retrieved 3 July 2022, from youtube.com.FUJIFILM X-T30 II | Cameras | FUJIFILM Digital Camera X Series [&] GFX – UK. FUJIFILM Digital Camera X Series [&] GFX – UK. (2022). Retrieved 3 July 2022, from fujifilm.com.

Quentin Tarantino and Roger Deakins Polarizing Opinions on Film VS Digital. (2021). [Video]. Retrieved 3 July 2022, from youtube.com.

X Series | Fujifilm [United Kingdom]. Fujifilm.com. (2022). Retrieved 3 July 2022, from fujifilm.com.